A highly respected business leader with an extensive record of accomplishment, Alan J. Lacy served as vice chair of the board and CEO of Sears Holding Corporation (created through the merger of Sears and Kmart) from 2005-06, and before that as chairman of the board and CEO of Sears, Roebuck and Co. from 2000-05. Before joining Sears, Lacy served in a variety of leadership positions at Kraft Foods, Inc. and Philip Morris Companies, Inc. (Kraft’s parent company after 1988). Since leaving Sears, Lacy served as Senior Adviser to Oak Hill Capital Partners from 2007-14. Currently he is a trustee of Fidelity Funds as well as the California chapter of the Nature Conservancy, and a director of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. He earned a bachelor’s degree in industrial management from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1975 and an MBA from Emory University in 1977.

Lacy currently lives in Pebble Beach, CA, with his wife Caron. Now in his second three-year term, he joined the CASBS board of directors in September 2015. We conducted a Q&A with Alan to learn more.

CASBS: Alan, before we get to more interesting stuff, we’re curious about your thoughts on your former company, Sears, which has been in the news a lot in recent months.

Alan Lacy: Needless to say, no one wanted Sears Holdings to be successful more than I did, but I’m not surprised by the outcome. Our management team had done a lot to improve the business, both in terms of merchandise offered and customer service. In 2004, we had just enjoyed a record year and were ranked third in our sector in Fortune’s “Most Admired Companies” ranking. We were ranked 10th when I became CEO in 2000.

That said, if I had had full confidence in the company’s future, I wouldn’t have sold it. Sears is really the last true department store. It’s a sector that has been in a state of decline for over 40 years. And it’s not over yet! In addition, unlike the other mall anchors, 70% of Sears revenues competed with big box formats like Walmart and Home Depot, which are off-mall, have larger assortments, lower cost structures, and had been growing their store base rapidly and closer to customers’ homes. We had been too focused on our mall locations and hadn’t properly faced this newer competition. The principal reason I sold was to accelerate off-mall growth by converting Kmart stores to the Sears brand. There was a window of opportunity the first 3-4 years after the sale to follow through with the strategy, but the new ownership didn’t, mostly because the company was overly focused on maximizing cash flow and share buybacks. When the Great Recession hit, that was pretty much the nail in the coffin. It may not have worked anyway, but the new owners took on that risk.

Also, while we had the best e-commerce capability of traditional retailers at that time, both as Sears and through our Lands’ End business, I don’t think anyone anticipated Amazon’s success. In 2005, Sears Holdings had more than $50 billion in revenue; Amazon had $8 billion. Today it’s $230 billion for Amazon, and Sears and many other retailers have been severely diminished or don’t exist. Our shareholders did well in the sale, but I do feel badly for our customers and employees. Retail is a tough industry.

C: You were born and raised in Cleveland, Tennessee, not far from Chattanooga. There’s so much natural beauty in that part of the country. Does your early life play a role in your more recent service as a Trustee of the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) and the California chapter of The Nature Conservancy (TNC)?

AL: The town I grew up in is in the valley created by the Tennessee River. I could see the first ridges of the Appalachians from my backyard. My family settled in the area in the early 1800’s. They were all farmers until my father moved into the town and worked in the retail industry for a small five and dime store chain. I didn’t really engage in the outdoors at that time, but growing up there did give me a sense of history and of place and an appreciation of natural beauty. My conservation interest really developed while I was in college in Atlanta. I got involved with Georgia Tech’s outdoor programs and did a lot of backpacking and white water canoeing in the Georgia, Tennessee and North Carolina mountains. Those were life changing experiences for me.

C: We found a photo of you from the 2000s that shows you with Clarence Page, Eddie Williams, Elliott Hall, and Vernon Jordan. You were at The Joint Center for Political Economic Studies in Washington, D.C., where Jordan was receiving its Louis E. Martin Great American Award. Being in that kind of company suggests an interest in social justice and equality.

AL: Yes, the Joint Center was an important organization to the advancement of the rights of minorities. Sears received an award from them as well. We had a 50-person all-volunteer, gospel choir comprised of Sears associates in Chicago, mostly African American, and brought them to D.C to perform at the event. It was very heartwarming to see.

I had several experiences along the way that formed my thinking on this. I’ll share a few. The small Southern town where I grew up in the 1950s and 60s had a small black population. Unusual for a town in my area. My high school was integrated. The city built a brand new high school just before my freshman year and the high school that served the predominately black section of town burned down in an arson fire just a few weeks before the new school opened. The city didn’t have the time or money to rebuild it and, therefore, maintain the separation. The valedictorian of the class a couple of years ahead of me was black and a great athlete and human being. He went to West Point for college. One of his brothers was in the class behind me. He and his girlfriend were the first interracial couple in high school.

As a kid, I’d spend almost all of my school breaks working in the retail business my dad worked for. I was making minimum wage, $1.65 an hour in those days, working next to people who were trying to feed a family on the same wage. I was so impressed at how hard they worked for the most basic of income. The warehouse loading dock manager was a black gentleman who would tell me stories about when he was younger and was a truck driver for the company. He told me about certain counties in the mountains where, if he was still on the road, driving through them at night he was at serious risk. So, early-on I got some good perspectives on some of the inequalities of life.

In my business life, I was in consumer goods and services my whole career. As a result, truly understanding the needs of women and minorities were important to our business. At Sears, the heads of the National Urban League and the National Council of La Raza were on our board. Almost half of my executive committee were women, and in the early 2000’s I also instituted domestic partner benefits for our same sex partner employees. That was a bit tricky because Disney had just done it and was being boycotted by the Southern Baptist Convention. Our business was challenged enough already and we were also in the process of a major overhaul of our in-store service model and eliminating 75,000 positions. We did it quietly at first, but were among the first retailers to do so.

C: What do you do for fun/hobbies?

AL: My standard answer to that is that I like to travel and enjoy nature, history, and golf. Living on the Monterey Peninsula is about as good as it gets on combining nature and golf. I’ve traveled a lot internationally, have visited all 50 states, and through my relationship with NPCA and the National Parks, I've been able see a lot of American history up close and personal. But, what I most enjoy is learning new things.

C: Did social science research and insights ever intersect with your role as Sears CEO and Chair? How about in other offices at Sears headquarters?

AL: Having spent my career in consumer goods and services, we wanted to understand consumer wants and needs and create products and services to satisfy them. As a result, we spent a lot of time and money doing research into how customers and, as importantly, non-customers, think about our products or services. While I didn’t think about this being an applied use of social sciences at the time, it certainly was. Consumers usually “want” more than they “need”. As a retailer, you are trying to create urgency and get someone to buy something they want, but may not really need at that moment in time.

In my food industry days at Kraft, the lower the economic circumstances of families, the more they valued national brands. While they couldn’t afford many luxuries in life, feeding their families the best brands was one way they felt they were doing their best to take care of them.

C: You left day-to-day business life in 2006. How and when did CASBS cross your radar? Why did joining its board interest you?

AL: I was approached about joining by Roberta Katz [a current CASBS director] and Bill Pade [a now-former CASBS director] as I was beginning to spend more time in California. Having spent my career trying to better understand consumer behavior and managing large organizations, which exhibit their own organizational behavior, I was intrigued by what CASBS does. I also hadn’t done anything in an academic environment, and needless to say, anything associated with Stanford gets your attention. I also reached out to friends on the boards of Stanford’s Woods Institute and Freeman Spogli Institute who said they found their roles very interesting.

It was my session with [CASBS director] Margaret [Levi], though, that sealed my interest. While the fellows program is at our core, I am very excited about the impact we are having through our various programs, especially in regards to how technology is impacting society. This is one of the most important opportunities and challenges humankind has ever faced.

C: You bring a lot of business acumen to the CASBS board. In fact, you co-lead the board’s development committee. Is it a breeze or a challenge working with numbers with several fewer zeroes on the end of them compared with your days at Sears?

AL: Ha! Yes, when I was CEO of Sears in the mid-2000’s our revenues were just over $50 billion, and as a current trustee of many of Fidelity’s mutual funds, we talk about the trillions of dollars they oversee for their clients. I’m also on the development committee for TNC’s $7 billion global capital campaign. However, I adopted the attitude long ago that I just need to think about an organization’s money the same way I do my own. It keeps things simple and focused.

C: Your development committee co-leader is Heather Munroe-Blum, an academic by training and a former president of McGill University (we’ve previously put the spotlight on her), in coordination with CASBS development director Susan Hansen. What’s it like working with them?

AL: It’s great! Needless to say, Susan is a pro at fundraising and knows Stanford and CASBS well. Heather understands academic institutions, the need to fundraise and how to steward donors and, being a former CASBS fellow herself [2013-14], she obviously knows the value of what CASBS does. My answer wouldn’t be complete, though, without including Margaret Levi in it. She’s our best fundraiser in this endeavor, having crafted the vision for CASBS that fundraising efforts support. She communicates it beautifully and with great passion.

C: The CASBS board convenes twice per year at CASBS. Among other things, the board members spread themselves across several tables and eat lunch with CASBS fellows. What are your takeaways from these lunches?

AL: Well, it’s the best perk of being on this board! I’m so impressed by the quality of our fellows, their commitment to their areas of expertise and desire to continually advance their thinking. The variety of projects, some very esoteric and others very wide ranging, are fascinating. I’m most excited about the conversations related to the expected impact of their work. While I’m certainly in favor of advancing academic thinking, my business background biases me toward results. I find the work they are doing supporting our major themes particularly interesting.

C: We came across another photo of you, while CEO of Sears, participating in an economic roundtable in Chicago. You’re sitting next to Don Evans, President George W. Bush’s Secretary of Commerce at the time, and near two other Bush chief economic advisors, Lawrence Lindsey and Glenn Hubbard. So you crossed paths with major policymakers and influencers. Now you don’t have to name names, but if you called-up the policymaker or influencer of your choice after finishing this Q&A, what would you impress upon her or him about CASBS?

AL: I think that governments and policy makers almost always underestimate the possibility of unintended consequences. They try to fix one issue and people either circumvent it or it doesn’t fully accomplish what they were trying to do. So I’d say bringing a social science perspective and research to policy making early-on can make a big difference in effectiveness. One doesn’t have to look much further than [1997-98 CASBS fellow and Nobel Prize winner] Richard Thaler’s work in behavioral economics to see the value-added from bringing a social science perspective to policy making.

As another example, at a CASBS board meeting a couple of years ago, one of the CASBS fellows I had lunch with – I believe it was [2015-16 fellow] Lynda Powell – is focusing on public health issues. This includes things like why patients don’t take their medicines as prescribed by their doctors and how the overall cost of healthcare could be significantly reduced if they just followed their doctor’s orders. Are patients trying to make their supplies last longer to save money, do they not fully understand how important this is, or just forgetful? She is trying improve how doctors communicate the necessity of this to their patients before discharging them. CASBS plays an important role in supporting these efforts.

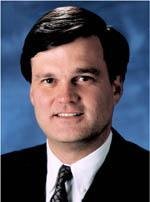

C: We can connect you with social science research! A 2009 article in Psychological Science explored baby faces and their correlations with success among black CEOs and white CEOs. A headshot photo of you, among others, was used in one of the study’s experiments. The article, we might add, cites serious scholarship, including work by former CASBS fellows Claude Steele, Michèle Lamont, and Linda Darling-Hamilton. Now, the results of that study were only suggestive, but we can attest right here, right now that you very much had a baby face in your Sears days:

AL: That’s very funny! I had heard about high correlations to being tall and becoming CEO, but not this. I’m 6’4” and about the only correlation I’ve noticed is that people ask me for directions a lot, or used to before map apps became so available. When I was in a new city for the first time, I would spend a little extra time studying the maps knowing I’d likely be asked for directions by someone.

More seriously, I was very fortunate to get to a senior level in my career at an early age. I became a VP of a Fortune 30 company at age 30. My direct reports were mostly in their 50’s. It’s not a term I would have used then, but I’ve tried to be “age blind” my whole career. I didn’t care if you were young or old. All that mattered was that you were capable and contributing. Needless at say, at age 65, I hope the baby face trait stays around for a while longer, but, alas, time marches on…