How CASBS Got Its Site

EDITOR’S NOTE: How and why is CASBS located where it is? The essay below, composed by two-time fellow Arnold Thackray (1973-74, 1983-84), tells the story and provides the answers. The essay first appeared in the 1987 CASBS Annual Report. It serves as a companion to the “prehistory of a history” CASBS origin story that Thackray published in the Center’s 1984 Annual Report. Read that story here.

A Site for CASBS: East or West?

Arnold Thackray has been invited by the Board of Trustees to write a history of the Center. The first article in this series appeared in the 1984 Annual Report.

In the early 1950s the Ford Foundation launched a major intellectual initiative in what it termed the behavioral sciences. To support that initiative it distributed unprecedented sums of money. The commitments of the foundation's new Division of Behavioral Sciences totaled 6½ million dollars in 1952 alone, dwarfing any previous philanthropic support for social science. Ford's actions, and the potential of its vast capital assets, attracted close scrutiny and lively speculation. We may understand the extent of the interest if we recall that the world of academic social science was then between a fifth and a tenth of its present size, and that the 1952 commitments by Ford exceeded in purchasing power the 1988 budget of the National Science Foundation's Division of Social and Economic Science.

Speculation focused most intensely on the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences that Ford was known to be planning. The question was not only "What will it be?" but also "Where will it be?" A campus fortunate enough to secure this jewel in the crown of behavioral science might expect both direct and collateral benefits.

Quite obviously, the Center would enjoy the services of those whom the foundation saw as the leading scholars of the day. To be the home of the Center would powerfully enhance a university's reputation and give access to an unrivaled flow of knowledge and information. Deciding on a site for the Center could hardly be easy for Ford. Choice among powerful, ardent, and diverse suitors would be painful. Choice was rendered more difficult by the curious fact that no one – not the president of the Ford Foundation, nor his senior staff, nor his consultants – knew exactly what the Center was to do, how it was to be organized, or for how long it might exist. These were matters to be settled in the future, and they would involve complex and delicate negotiation. All that was clear was that the Center was the main element in a bold pro gram of a newly rich foundation committed to dealing with the problems of American society.

The challenges ahead were more or less clearly understood by the members of the Center's "Board designate" as they assembled for their first meeting on January 22, 1953. The meeting took place in the East, at the Ford Foundations headquarters in New York City. And the Board itself had a distinctly Eastern look: the provosts of Harvard and Cornell (Paul Buck and F. F. "Frosty" Hill), a Columbia sociologist (Robert K. Merton), a Harvard psychologist (Robert R. Sears), and the director of the National Science Foundation (Alan T. Waterman). True, the Board also included one resident of Detroit (Theodore Yntema, a vice president of the Ford Motor Company), and one voice from the West (Clark Kerr, Chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley).1 But the locale and the personnel little suggested that barely eighteen months later this Board would have in operation a Center of a distinctly Californian design, on the grounds of Stanford University.

As suggested earlier in this Report, location and design have been central factors in shaping the Center's success and its enduring character. How did they come about? Both are clear examples of happy accident. Yet both cases were not so accidental as might at first appear. A certain serendipity was at work, favoring a California location and a novel design. The story of choosing a site for CASBS reveals how small and seemingly minor events can lead to major and enduring outcomes.

In June 1952 the Ford Foundation trustees voted for "the establishment of a Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences as an independent non-profit corporation." They had a tightly argued report before them as they voted, which made it plain that although the Center should cultivate close and harmonious relations with universities, it should not be an integral part of any university. More than that, "the Center should not be located on the campus of a major university because of possible distractions, requests for service, institutional jealousies, and the like!” Also, it would be preferable to locate the Center in a suburb or a small town so as to avoid "the distracting and diffusing atmosphere of a large city." The report recommended that the Center should be located near a major university for easy access to library and other relevant facilities, and that it "should be located in the East because of the concentration of the relevant personnel and institutions in that part of the country."2

The logic was clear. The East (meaning the Boston-to-Philadelphia corridor) was correctly identified as the home of a self-sustaining elite in the humanities and social sciences and of the resources necessary to its sustenance. Travel to or from other regions of the country and communication with them would be slow and difficult. This logic allowed little room for the pull of the California climate, for the dramatic movement of population in the post-war era, for the commitment of Western administrators to institution building, or for the new options in air travel.

The authors of the 1952 report believed that the Center might open in the summer of 1953. In fact, progress was much slower than anticipated, and there was little action to show by January 1953. The Board of Directors was, however, presented with "an informal survey of possible sites for the Center," which the Ford Foundation had commissioned. That survey was based on the criteria enumerated in the June 1952 report. It envisioned Center buildings of approximately 20,000 square feet.

New construction threatened to be expensive. An obvious solution was "a number of large estates for sale or lease along the Eastern seaboard." Leasing was an especially attractive option, as the initial Ford grant was to be for $3,500,000 expendable over five years. And no one was quite clear about what would or should happen at the end of that time. Accordingly, the survey focused on "the type of housing most likely to meet the needs of the Center, i.e., a large suburban home, preferably on an estate which contained guest cottages, servant quarters or other buildings; a moderate size sanitarium or rest home; a boarding school or small college; or a suburban hotel or inn."

The implicit assumption was also made that proximity to a major university meant the Boston, New York, or Philadelphia suburbs. Reconnoitering on the ground quickly made it clear that Boston and Philadelphia were far cheaper than New York; the survey mentioned that the Princeton and New Haven areas offered other possibilities. One final thought was that of "leasing or purchasing a suitable apartment building to provide living accommodations" for scholars not housed in the Center itself. A survey of more than a hundred properties identified fourteen that were appropriate: five each in the New York and Philadelphia areas, and four in the Boston suburbs.3

In the discussion that followed, Paul Buck quickly fostered the interests of Harvard by pointing out that it had available "the Cameron Forbes estate in Norwood, Massachusetts, which might be suitable." But majority sentiment favored the New York suburbs, despite the expense. In a first foreshadowing of the final outcome, Buck's fellow faculty member Robert Sears questioned the wisdom of the planning group decision to limit possible locations to the East Coast. Making an ingenious virtue out of intractable reality, he pointed out that the West Coast would have the advantage of protecting Fellows from other commitments, "since it was so far from where most of them would come." (Sears himself had been a Stanford undergraduate, and though a Harvard professor, he was considering a return to Stanford.) His argument was felt to have some merit. The Chairman of the Board, Frank Stanton, closed the discussion with the tactful thought that progress on the site could best be made after a director was appointed, since the director's advice would be important.4

Within the week, Paul Buck sent a letter describing the Cameron Forbes estate. He stressed that “a rental arrangement with option to buy might prove possible and constitute an advantage.”5 Mindful of the differences in viewpoint, Stanton moved to create a special committee on the Center's site with Hill as chair and Kerr and Yntema as the other members. Bernard Berelson, Director of the Behavioral Sciences Division at Ford, and Stanton himself would be unofficial participants. Buck, Merton, and Sears would be safely diverted to the other special committee, charged to select the Center's first director.6 Meanwhile, the official press release announcing the appointment of the Center's Board stimulated some alert university presidents to write to Stanton advocating the charms of available space on their campuses. At this stage, Stanton was sanguine that a site would be found by April at the latest.7

A meeting of the site committee was called for April 3, immediately before the second meeting of the Board. The chairman of the committee, Frosty Hill, felt it wise to move slowly and to postpone selection of the site until the director was appointed. He also wrote Clark Kerr that it would be appropriate to review the criteria developed in the June 1952 report and to discuss whether the Center should be located in the East, or somewhere on the West Coast.8 On April 3, 1953, the CASBS Board approved Ralph Tyler as the Center's first director. It also heard from the site committee that "suitable sites were available both on the East and West Coasts, and that the desires of senior and junior fellows, cost, and accessibility" were factors to be taken into account. Rowan Gaither was among those attending the meeting.9 As author of the initial study that had emphasized Ford's opportunity to carve out a special niche in social science, he was certainly interested in CASBS. As the newly elected president of the Ford Foundation, he was in a position to assert authoritatively that the Center was of major interest to the foundation as a critical part of its program for increasing scientific knowledge of human behavior. As an alumnus of Berkeley and long-time resident of the Bay Area, he was not unaware of West Coast attractions. No more were Board members unaware of his provenance.

Here matters stood for three months. The Board met once more on June 30, 1953, in New York, with the new director present. Tyler officially accepted his appointment and "reported that he would prefer to work out of Chicago until the site was selected.” Subtly and no doubt unconsciously, the Boards eyes were turning westward.

With Ralph Tyler present, the style of discussion began to change. At the June 30 meeting, he reported to the Board that "scattered polling of scholars had as yet indicated no clear preferences as to geographical location." But the westward shift was again apparent in his revealingly ordered statement that "the San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, New York and Philadelphia areas all had their supporters."

A luncheon-recess meeting of the site selection committee allowed it to present to the Board a new set of criteria for the site. The Center was no longer to be located in relation to the concentration of relevant personnel, but rather in relation to seven factors. Six might be met easily in the suburbs of any major city ("good schools," "ease of transportation," etc.). The seventh factor was somewhat different. It was the one word "climate." The Board urged the committee to proceed as rapidly as possible, and expressed the hope that the October meeting of the Board might be held "in the same area as the proposed site so that it could be inspected by the Board."10

If where the Center was to be remained unclear, what it was to be was also far from settled. The original survey of possible sites had proceeded on the assumption that the Center would have twelve senior Fellows, each with an office of approximately 225 square feet, and thirty-five junior Fellows, each with a "space" of approximately 65 square feet. By the time of its June 30 meeting, the Board was convinced that the "senior-junior" distinction should be played down. Building on, and moving decisively beyond that thought, on July 13 Tyler wrote to the Center's real estate consultant that "a distinction between 'seniors' and 'juniors' is unwise. All are to be Fellows working together with a common purpose." Hence 45-50 private offices would be needed for 45-50 Fellows. For this and other reasons (e.g., more secretarial staff), the Center would need not 20,000 but 30,000-35,000 square feet of space.

The consultant accordingly reported that of the fourteen properties identified earlier, ten were still suitable and available (four in the New York area, two in the Philadelphia area, and four near Boston). Three in particular were fully appropriate, two from New York and one from Philadelphia. There was comfortable time to negotiate a lease, develop architectural plans, and undertake required modifications of existing buildings before the scheduled opening of the Center in summer 1954.11

Apparently, the Center's needs could be met quite easily by any of these three sites in the East. But Ralph Tyler was willing to live with uncertainty while he explored other options. On July 14 he sent a letter to several scholars, briefly explaining the Center's rationale ("an opportunity for scholars ... to spend one or two years ... extending their knowledge of human behavior"), naming the five metropolitan areas under consideration, and asking, "Of the five possible locations, at which would you prefer to spend a period of a year or two ?"12 Meanwhile, the real estate consultant wrote that he was enthusiastic about several of the properties that had turned up in and near San Francisco.13

Tyler had already arranged for the site committee to view the two most promising eastern sites (the Mary Lyons School, abutting the Swarthmore campus, and the Brigham estate in Hartsdale, Westchester County, New York) on September 2 and to visit San Francisco later that month.14 The second of September was a hot and humid day in the East. Even so, the site committee found Swarthmore attractive. The property itself, however, was in poor condition; wholly new construction might be needed. The possible expense, the steadily shortening time-scale, and uncertainties over the Center's long-term future made new construction seem unattractive. Yet it could not be ruled out.

At this point, "it was decided by Mr. Stanton that the whole Board should have a chance to see the available sites around San Francisco before reaching a decision." Tyler went ahead to scout out the territory,15enlisting the aid of Clark Kerr and Robert Sears (by then in residence at Stanford as executive head of the psychology department). Meanwhile other possibilities were introduced. Lafayette College (Easton, Pennsylvania) wanted to put up a building especially for the Center. Frosty Hill, chairman of the site committee, suggested that Cornell could do likewise.16

When the Board met in San Francisco on October 9, invitations to the Center for the fall of 1954 had already gone out to eighteen potential Fellows. The only problem was that there was no Center. Discussion ranged over the five previously discussed metropolitan areas, plus Denver. The twenty-one replies to Tyler's poll revealed "a preference for the San Francisco area, with New York second, and Philadelphia third. Only two wanted a site near home." Discussion reverted to the importance of a "comfortable year round climate."

The Board visited three sites, one in Millbrae, one in Belmont, and the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. It agreed to take the necessary steps preliminary to making an offer for the School of Fine Arts.17Rowan Gaither wrote to Stanton on October 16 to say, "I take it that San Francisco will be the site for the Center. If I applaud this decision I will be charged with provincial bias....I shall leave it to you and the other members of the Board to guess how I really feel."18 The quest seemed at an end.

Late in October Ralph Tyler conducted a series of telephone conversations with a "selected group of senior Fellows: re California for the Center site." Clyde Kluckhohn was highly favorable to San Francisco; John Dollard, Joseph Spengler, and Samuel Stouffer were undecided. Herbert Simon and Edward Shils both preferred Philadelphia, but thought San Francisco acceptable (Simon judged it "isolated"). Paul Lazarsfeld was more outspoken. The fog would mean one "can hardly ever work outside," and the long commute back east would be a problem. "As we came nearer to the reality of the West Coast, we found the resistance growing up." Opinion was far from unanimous. Nonetheless a poll of the Board revealed only one member definitely opposed to the purchase of the San Francisco property.

At this point, reality intruded. In mid-November the trustees of the School of Fine Arts decided not to sell, after all. The committee reverted to Swarthmore, but was unable to agree on satisfactory terms. The Forbes estate was again advocated by Paul Buck and visited by Robert Merton, who was attracted to it, but the buildings were not large enough. "At this point Gilbert White, President at Haverford College, located two estates a mile from the College which could be purchased." Berelson, Hill, Stanton, and Tyler paid them a hurried visit. They were all "much impressed" by one (the Reeve) estate, and felt it to be "the best one we had thus far seen." A contractor was engaged to prepare estimates on remodeling. Katherine McBride, President of Bryn Mawr, declared that "the Main Line was delighted with its prospect of having the Director as a resident."

The Center was apparently heading back east. Undaunted, Kerr and Sears took up the previously neglected theme of constructing "a modest office building" in the San Francisco area. Kerr undertook to look into possible sites and construction costs. "Furthermore, Sears located several possible building sites in the San Francisco area."19

The year 1953 was drawing to a close. Invitations to the Center were being issued and accepted. But the Center itself hovered like a will-o'-the-wisp, uncertain whether to alight in the East or the West. As early as October 12, Frank Stanton noted that "our lack of finality on this important subject is beginning to plague our planning."20 Trustees less secure than Stanton and Tyler might well have settled on the one identified, acceptable set of buildings in Haverford. Instead, the search continued.

The Center Board held its fifth meeting on January 2, 1954, in New York. Discussion of the site was by now a major item. Abandoning a neutral role, Stanton made it plain that he favored a West Coast location. Although the California School of Fine Arts would have been ideal, being in reach of Berkeley and Stanford but remote from both, four other possible sites had been identified. One, in Menlo Park, was judged "a little close to Stanford." The best option was the Crocker estate in Hillsborough, which Clark Kerr had brought to the Board's attention as early as February 27, 1953.21 Its owner was sympathetic to social science, and anxious to offer favorable terms.

Following some rear-guard efforts on behalf of an Eastern location, the Board voted to incorporate itself in California (to facilitate negotiations) and to purchase or acquire the Crocker estate. Once more, all seemed set. Apparently as an afterthought, "Mr. Sears suggested that since he lives in the area, he might transfer his membership from the subcommittee on personnel to the subcommittee on site" (replacing Yntema). Thus, at a crucial moment, the committee on the site gained both a California majority and the original California advocate.22

The Board reassembled in California (San Mateo) on Saturday and Sunday, February 12 and 13. One purpose was to view the Crocker estate. The Board also had before it an engineer's estimate testifying to the essential soundness of "The Crocker 'New Place,"' but indicating that $100,000 would need to be spent on renovations and adaptations. Doubts sur faced. A decision was postponed while a quick trip was made to a possible alternative site. The Board took Saturday lunch with the City Council of Hillsborough, which agreed to introduce a motion for a zoning variance for the Crocker estate the very next Monday.

After lunch the doubts refused to go away. If the Board had an image of the Center, it was of a source of innovation, of modernity, of revolutionary (but peaceful) thought. Hillsborough was one of the richest, most staid, and slowest-moving suburbs in the whole Bay Area. "Mr. Stanton said he was concerned about the Center fitting into the Hillsborough community." Ralph Tyler, faced by the unassailable need to have a building if the Center was to open, "thought the Hillsborough people would not actually have much contact with the Center or the people at the Center." Edwin Huddleson, brought aboard as the Center's attorney in connection with the California incorporation (he was a partner in Rowan Gaither's old firm in San Francisco), said that "although Hillsborough is a definitely conservative area, they have a very active young Republican group."

In an unusual action, the Board split down the middle. Four voted for Hillsborough, and five for constructing a new building on an unspecified site. The decision on whether to purchase the Hillsborough estate or to find a new site was left to those able to stay over to Sunday.23 The idea that the Center had certain design needs that should not be compromised was gaining ground.

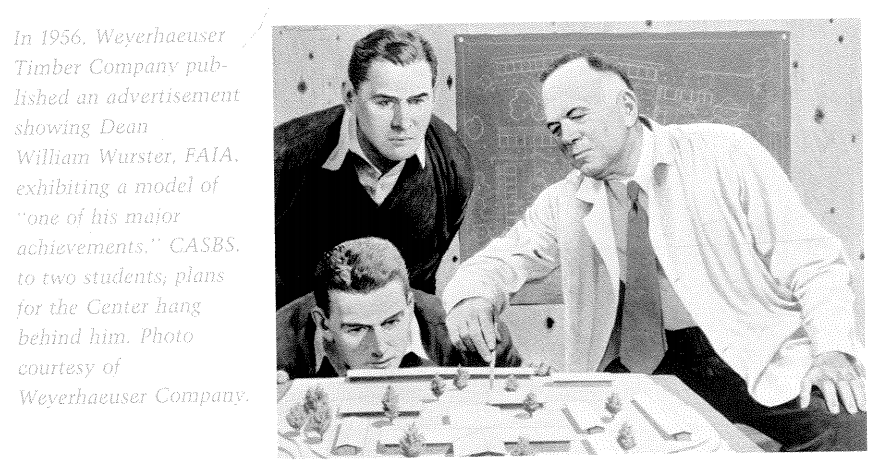

The remnant of the Board made a somewhat desperate examination of possible sites in the East Bay area and San Francisco on the Sunday morning. The results were not encouraging. The group did find "a beautiful site back of the California School for the Blind.” The idea of building was briefly discussed. But "Dean Worcester [i.e., William Wurster] of the College of Architecture told us that ... we could hardly expect a building completed in less than nine months, even under overtime provisions." With this fact before them, the remaining nucleus of the Board agreed to give up the idea of building, since a significant group of Fellows was already signed up for September 1954. If the unthinkable were to happen and a zoning variance were denied, then "we shall try to postpone the opening for a year" despite the "bad effect in morale and increase [in] our costs."24 Edwin Huddleson expressed confidence that the necessary zoning variance would be forthcoming. The decision was made to purchase and remodel the "New Place" on the Crocker estate.

The agonizing and the decision were in vain. The unthinkable happened. Ironically justifying the Board's doubts about Hillsborough, the City Council had doubts about a swarm of social scientists. It voted to deny a zoning variance.

At this stage, matters were becoming serious. The hoped-for opening of the Center was little more than six months away. The first Fellows were mentally packing their bags. Yet there was no Center, and no site for one. Interestingly, the Eastern conversations were not re-opened, even though Haverford and Lafayette had both made attractive offers. California, the Bay Area, and the advantages of climate had apparently caught the Board's collective imagination. In any event, the Californian majority on the site committee chose to see things that way, and Ralph Tyler did not dissent.

After learning of the action of the Hillsborough City Council, Clark Kerr and Robert Sears immediately sought other sites. Kerr was able to bring to bear the resources of his office to dig out "possible buildings and available land." Not surprisingly, his focus was on the East Bay. Meanwhile, Sears pursued sites on the Peninsula.25

By the time Ralph Tyler arrived in San Francisco on February 27, nine possible sets of buildings had been identified. On March 1, a "rump" group consisting of Hill, Berelson, Kerr, Merton, and Stanton met in Stanton's office in New York. That group ratified the search already under way. By March 4 Ralph Tyler was ready to report. Five of the nine sites could be dismissed. Of the remaining four, the Sharon estate in Atherton "has the most beautiful view of all places we have seen. It is high above the Bay about three miles northwest of Stanford, with no other houses within a mile." Tyler ranked the Sharon estate lowest, because of its distance from public transportation.

Also attractive was the five-building campus of Williams College in North Berkeley. The location was excellent – in the Berkeley hills only two miles from the University of California. But the main building would be difficult to remodel for offices, the threeacre site was somewhat crowded, and the zoning situation was uncertain.

The prospects appeared more promising at the Infant Shelter at Ortega Street and 19th Avenue in San Francisco, "an institutional building, large enough for our purposes and in excellent condition." The only obvious snag was that the shelter was "west of Twin Peaks in the fog belt." In a reversal of the principles long adopted by the Ford Foundation and the Board, Tyler also argued that "it does not give the advantages to the Center Fellows that nearness to a university would give them." What exactly the director had in mind is not clear, as the Infant Shelter was comfortably within an hour of both Stanford and Berkeley – just the sort of distance aimed at in earlier discussions.

Perhaps the answer was simply that Tyler had at last seen his dream site and needed to justify it. "My own first choice is the Lathrop estate. It is on a sunny site with a fine view overlooking Stanford and the Bay. It is a mile from the University alone on a high hill, thus assuring a good deal of privacy. Its post office is Menlo Park." An added lure was that Stanford would rent out the site for the first five years, at a dollar a year. The chief disadvantage was "the bad architectural design" of the Lathrop property. The main house, "Alta Vista," and its various outbuildings could be remodeled, however, to give interesting clusters of offices and seminar rooms.

In his report, which commended both the Infant Shelter and the Lathrop estate but made the Lathrop estate first choice, Ralph Tyler finessed the last remaining problem: "We have always had as one criterion for site selection a requirement that the site be near but not on a campus of a major university. This site is close to Stanford but not on the campus." And in a sentence that possesses a certain period charm, he concluded by saying, "The attitude of some university people that certain major universities are already over-favored by foundations and government contracts does not generally include Stanford."26

The Board, short of options and aware that Rowan Gaither would not be unhappy, agreed with Tyler's assessment. The saga is best continued in the words of William Wurster. Together with Clark Kerr, Ralph Tyler, and Robert Sears, he visited the Lathrop estate and its "truly undistinguished old wooden threestory structure" on a Sunday morning (March 6). The group was no doubt mindful of Wurster's earlier statement about the impossibility of constructing new buildings in time.

There was talk of remodeling Alta Vista for over $200,000. I held myself in until we were having lunch several hours later at Chancellor Clark Kerr's house in Berkeley. When asked my opinion I burst out bluntly: "Tear the damned old house down-build the motel type of one story thing so much used in California. This will enable hundreds of workmen to be at the site and not be in each other's way while, if you remodel, each trade waits on the other in an intricate structure of many floors. And anyway, who wants to be up three stories, in a hot attic, to hear the pecking of the typewriter through the wood floors!"

"But the time element!" they asked.

"O.K., here it is the sixth of March, bids in six weeks, start building in two months, four months building, complete in six months."

And we did it! 27

Pressure of circumstance thus combined with a noted architect's feel for the California idiom to produce buildings superbly suited to the Center's unique blend of privacy and community, in a way that capitalized on the topography, the climate, and the view. The rest of the story may be told quickly. The Stanford University trustees were agreeable to a fiveyear, renewable lease, which sat well with the Center's uncertain future. Within two weeks of the meeting in Clark Kerr's house, the firm of Wurster, Bernardi and Emmons was formally authorized to develop plans, and the Stanford trustees had approved the proposal in principle. Florence Knoll of New York was engaged as interior decorator, and it was stressed that "the fellows coming to the Center would want simple, light attractive furniture and decoration somewhat on the austere side." Interestingly, the size of the Center, which had grown from 20,000 to 35,000 square feet in earlier discussions, was now down below 20,000 square feet again. An emphasis was placed on providing structures "which would last at least thirty years."28

By April 21, plans were complete, the wrecking of Alta Vista was under way, and a timetable for the new construction had been agreed. The only problem was that the cost of the whole venture threatened to reach half-a-million dollars, or roughly double what had been anticipated. Heroic measures were called for. Thirteen studies, two seminar rooms, and a room for stenographers were temporarily stricken from the plan (only 30-35 Fellows were expected for the Center's first year).29

Construction finally began on May 17, 1954. The Center had a site.

Notes

- In Agenda papers, CASBS Board, 22 fan 53, Stanton files.

- Summary report on potential sites, CASBS Board, 22 fan 53, Stanton files.

- Summary report, p. 9; see also full report, CASBS Archives I, 13.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 22 fan 53, Archives I, 20.

- P. Buck to F. Stanton, 24 fan 53, Stanton files.

- Various telegrams, in Stanton files.

- Hurst R. Anderson to F. Stanton, 5 Feb 53; F. Stanton to B. Berelson, 7 Mar 53, Stanton files. Other institutions entering the fray included the University of Vermont, St. Michael's College, Vermont, the University of Tennessee, the University of Illinois, and the University of Oklahoma.

- F. F. Hill to C. Kerr, 25 Mar 53, Stanton files.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 3 April 53, Archives I, 20.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 30 fune 53, Archives, I, 20.

- Report of M. H. L. Sanders, fr., August 53, Archives, I, 13.

- R. W. Tyler to f. Dollard, 14 fuly 53, Archives, I, 13. Identical letters went to K. Boulding, L. Festinger, E. Frenkel-Brunswik, V. 0. Key, C. Kluckhohn, N. Miller, T. Schultz, and f. W. M. Whiting.

- M. H. L. Sanders, fr. to R. W. Tyler, 28 August 53. The real estate consultant, chosen by Gaither in 1952, lived in the San Francisco region and was most familiar with property there.

- R. W. Tyler to F. F. I, 13. 24 Aug 53, Archives, I, 13.

- Notes on meeting of site committee, 2 Sep 53, Archives, I, 13.

- F. F. Hill to F. Stanton et al., 18 Sep 53, Archives, I, 13.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 9-10 Oct 53, Archives, I, 20. See also Alan T. Waterman papers, Library of Congress.

- H. R. Gaither to F. Stanton, 16 Oct 53, Stanton files.

- Progress report of the committee on site, l7 Dec 53; M. H. L. Sanders to R. W. Tyler, 5 Dec 53, Sanders file, Archives, I, 13; notes on tele phone conversations, 23 Oct 53, and notes of a visit, 1 Dec 53, Archives, I, 17.

- F. Stanton to P. Buck, 12 Oct 53, Stanton files.

- C. Kerr to B. Berelson, 23 Feb 53, "Site-California-Crocker" file, Archives I, 13.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 2 fan 54, Archives I, 20.

- Minutes of CASBS Board, 12-13 Feb 54, Archives I, 20.

- R. W. Tyler to A. T. Waterman, 16 Feb 54, Archives, I, 24. Wurster, the dean of the Berkeley architecture school, was co-opted to the exploratory group by Clark Kerr.

- M. H. L. Sanders file, Archives I, 13.

- Report on available buildings, 4 Mar 53, Archives I, 13.

- Quoted from Architectural Forum January 1955, pp. 130-131. See also the 12 Mar 54 memo "Site for Center" in Alan T. Waterman papers, Library of Congress.

- R. W. Tyler to committee on business affairs, 22 Mar 54, Archives I, 13; R. W. Tyler to members of the site committee, 23 Mar 54, Archives, I, 13.

- R. W. Tyler to CASBS Board, 21 Apr 54, Archives I, 13.