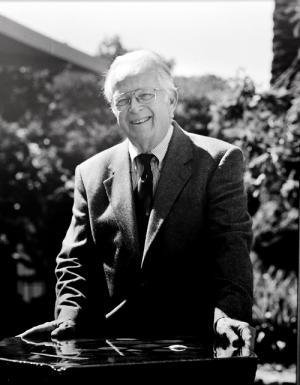

Neil Smelser, Distinguished Sociologist and Former CASBS Director (1930-2017)

Neil Smelser, one of the most influential sociologists of his time, passed away at the age of 87 on October 2, 2017.

Celebrated for his work on sociological theory as applied to economic institutions, collective behavior, social change, and personality, Smelser is widely credited as a foundational figure in developing, among others, the field of economic sociology.

Smelser’s obituary, composed by his daughter, Sarah, appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle on November 12, 2017. Smelser’s home institution, the University of California, Berkeley, published an obituary on October 12. It notes that Smelser also acted as a liaison between the university administration and student groups, and deftly “navigated the swells of student uprisings during the exhilarating and tumultuous 1960s…”

Smelser spent nearly the entirety of his distinguished career at UC Berkeley. A Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford, he earned his PhD from Harvard University in 1958. He was a professor in sociology at UC Berkeley, attained the prestigious position of University Professor in 1972, and later University Professor Emeritus of sociology (1994).

From 1994-2001, though, Smelser crossed San Francisco Bay to serve as the fifth director of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS).

Bob Scott, CASBS associate director during Neil Smelser's tenure, composed a remembrance of Smelser and CASBS under his directorship. Read it here. Read remembrances from former CASBS fellows at the end of this article.

UC Berkeley’s obituary broadly credits Smelser as “an outspoken and influential advocate for social and behavioral sciences…” He co-edited, with Paul Baltes, the multi-volume International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2001), a copy of which resides in CASBS’s Ralph W. Tyler Collection. A copy of his book co-authored with John Reed, Usable Social Science (2012), as well as his book co-edited with Dean Gerstein, Behavioral and Social Science: Fifty Years of Discovery (1986), also reside in the Center’s Tyler Collection.

Smelser also served as the 88th president of the American Sociological Association in 1997. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, The American Academy of Political and Social Science, and the American Philosophical Society.

Some of Smelser’s most noted works include Economy and Society (1956), Social Change in the Industrial Revolution (1961), Theory of Collective Behavior (1962), The Sociology of Economic Life (1963), Social Paralysis and Social Change (1991), Problematics of Sociology (1997), The Social Edges of Psychoanalysis (1998), The Faces of Terrorism: Social and Psychological Dimensions (2007), and Dynamics of the Contemporary University (2013).

Read tributes and remembrances by the American Academy of Political and Social Science, the Russell Sage Foundation, Social Science Space, and UC Berkeley’s sociology department – which itself compiled remembrances from some of Smelser’s former students and colleagues.

Read transcripts of interviews with Neil Smelser, conducted in 2011 and 2012 for the UC Berkeley Oral History Center, here.

View a 2011 video interview, “Intellectual Odyssey, with Neil Smelser,” produced by University of California Television, here.

Former CASBS Fellows Remember Neil Smelser

Do you have a remembrance of Neil Smelser? Please send it to casbs-news@stanford.edu and we will post it below.

Ute Frevert (2000-01)

It came as a shock to hear about Neil’s death – and it brought to my mind our first personal encounter, back in 1999. As a newly elected member, I attended a meeting of the German-American Academic Council (which was soon thereafter dissolved because of financial mismanagement), and I was seated next to Neil. Looking at his nameplate, I could not believe my eyes – and I blurted out, without thinking: “I thought you were long dead!” Neil burst out laughing and could not stop laughing for a while. When he finally managed to catch his breath, I, blushing deeply, had the chance to explain and apologize. For me, Neil Smelser’s Social Change in the Industrial Revolution, published in 1961, was a true classic; I had bought it, as a student, at the LSE bookstore in 1974 (I still remember its light bluish jacket). With a quick calculation twenty-five years later, I assumed that the author of such a classic should have passed away a long time ago. Neil good-humoredly convinced me that this was not the case. But he never forgot about the incident, and it became something of a running joke between the two of us. During my stay at CASBS, I was fortunate to experience his intellectual vitality and human warmth. It made my year there beautiful and unforgettable.

Gary Marx (1987-88, 1996-97)

provides a lengthy tribute here.

Donald S. Lamm (1998-99)

On the Wednesday evening seminars at CASBS, Neil Smelser’s remarkable intellectual reach was on full display. At first I wondered how closely he could attend a fellow’s presentation as he inked Wedgwood designs onto the styrofoam cup inevitably held in his hand. But once the speaker subsided, it was Neil who asked the pertinent question that went to the core of the presentation. Indeed, Neil’s intervention could be counted on to clarify the preceding remarks. Never did any of us doubt that we were In the presence of a renowned scholar who also happened to be a master teacher.

Together with his wife, Sharin, Neil hosted many a congenial gathering at the director’s house off Junipero Serra Blvd. One could not imagine a leader better suited to make a year at CASBS an unforgettable experience.

Piotr Sztompka (1998-99)

It is a great gift of fate when the academic master turns into a friend. This was my experience with Neil J. Smelser. Just three examples of his immense generosity and trust from a sociologist from a far away country, Poland.

When I first came to UC Berkeley as a Fulbright post-doctoral fellow in 1972, the first thing I did was enroll in Neil's class on classical sociological theories. I was with Jeff Alexander, Eric Olin Wright, Luca Perone, and others listening to Neil's masterful lectures. When, after Comte and Spencer we arrived at Karl Marx, Neil approached me and asked if I could deliver the lecture in his place. I did and it was a most memorable event in my long teaching career. When, at the end of my fellowship I completed the manuscript of my first English-language book on structural-functionalism, it was Neil who recommended it to Stanley Holwith, then the editor at Academic Press. The book System and Function was published a year later, introducing me to the American sociological community and initiating my international career.

More than twenty years later I came as a fellow to CASBS, where Neil was director. Unfortunately, during that time my mother became very ill and I had to return to Poland. Some months later, a bit contrary to standard CASBS policy, Neil invited me back to complete my fellowship. The eventual result was a book coauthored by Alexander, Eyerman, Giesen, Smelser, and myself on Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity.

Some twenty years passed and in 2014, at the age of 70, I retired from the Jagiellonian University at Krakow. Instead of the traditional Festschrift, the faculty's idea was to invite some of my foreign colleagues and collaborators to deliver a series of visiting lectures ("oral publications" on their current work) for our students. When the time came, incredibly, I found myself at the Krakow airport greeting Neil, who came off the plane in a wheelchair after a long flight from California. He took this huge trip and withstood a great deal of discomfort, just for the sake of one of his 1970s students.

Of course in between these snapshots in time I had many more opportunities to meet and collaborate with Neil (for example, in various capacities within the International Sociological Association, where eventually I succeeded him as president). But the three episodes outlined here evoke the strongest emotions of gratitude and show best what kind of person Neil Smelser was.

Christine Williams (1995-96)

I was fortunate to be a CASBS fellow right after Neil became Director. Neil was my dissertation supervisor at Berkeley ten years earlier, and he was the same open-minded engaging intellectual I knew then. I can still picture us discussing research in his beautiful office at the Center. He was expert at drawing connections, suggesting new angles, and making comparisons to sharpen the theoretical point. Our academic interests were diverse, but we shared a subversive passion for psychoanalysis. We goaded each other to use the theory more in our sociological work. When Neil decided that year to make ambivalence the theme of his ASA Presidential Address, I considered it a personal victory. Paradoxically, Neil was the least ambivalent sociologist I have ever known, a view shared by many of his students. When Jeff Alexander, Gary Marx, and I published a festschrift for Neil in 2004, we titled our introductory essay “Mastering Ambivalence” to honor his penchant for synthesis. Neil was the quintessential academic peacemaker, but he taught us that acknowledging the warring forces inside the individual is key to achieving a deeper and richer understanding of social life. Judging by his example, it may also be key to achieving a deeper and richer life. He was a superb teacher, role model, and friend, and I miss him very much.

Jeffrey C. Alexander (1998-99)

Neil Smelser was an extraordinarily effective CASBS Director, without doubt the most gifted academic administrator under which I have had the privilege of serving during my five-decade academic career. He quietly, assiduously, and attentively attended every weekly fellows' lecture, waiting patiently to ask his penetrating, often challenging, but always good-natured questions. He was a cheerful and encouraging leader, an academic who had studied, even practiced, every discipline represented among the fellowship. Neil had a wry but ever-present humor, an almost preternatural calm, and also, when the occasion demanded, a steely and effective disposition. Let me recount one small, but I imagine representative, example.

During the middle of the 1990s, Neil called me at UCLA from CASBS to make a proposition that no overworked, over-administered, teaching-overloaded, publicly employed academic could refuse: Would I work with him on a three-year, Hewlett Foundation-funded project, the last year to be spent at CASBS, with a research team of like-minded fellows, identified by myself? Fast forward to the Palo Alto hills and CASBS, 1998-99, and to the assembled research "dream team" on cultural trauma with Neil himself a charter, if not continuously present, member.

The catch: A bit of friction between two members of the group threatened the project. The topic of cultural trauma had become the experience of it, inside CASBS itself. After unsuccessful mediation, I made an appointment with the director. As I began explaining the situation to him, Neil interrupted -- "Jeff, there's no need to elaborate. I already know exactly what you're talking about. I've seen it developing myself." Then, he followed up: "Let me say something, completely off the record, to the parties involved." I breathed a giant sigh of relief, and allowed myself more than a small bit of hope. A couple of days later, Neil gave me a discrete nod. Our small research team went along quite smoothly from that day forward. We wrote a collective book, Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, which established a small but sturdy paradigm for research that continues today. Neil contributed to that academic publication, but his most important contribution came earlier, when he secured its interpersonal foundation.