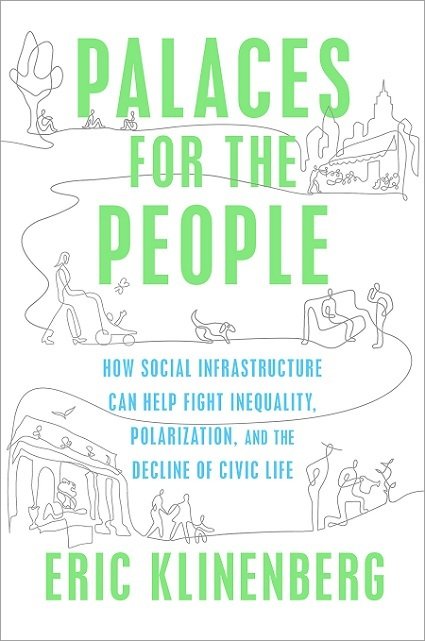

Two-time CASBS fellow and NYU sociology professor Eric Klinenberg released his latest book – Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (Crown Publishing) – in September 2018.

He wrote most of it at the Center during his second stint as a fellow in 2016-17. In the book Klinenberg makes the case for “social infrastructure” – the physical places and organizations that shape the way people interact – as a “missing piece of the puzzle” in building or re-building the places where people can gather to repair the “fractured” societies and “precarious” social order we live in today. Examples of such shared places include bookstores, churches, public parks and libraries, childcare centers, and other places where inclusive social connections form. In chapters devoted to health, education, public safety, climate change, political polarization, and more, Klinenberg explores and explains how the social and physical environment can promote – or undermine – civic cohesion. This environment “shapes our behavior in ways we’ve failed to recognize; it helps make us who we are and determines how we live.” Ultimately, the social infrastructure we build or fail to build in the years ahead “will tell future generations who we are and how we see the world today.”

We recently caught-up with Eric as he continues a whirlwind tour talking about ideas contained in the book. He was kind enough to pause for a moment and answer a few questions.

CASBS: Eric, perusing your Twitter feed we notice you’ve done a fair amount of traveling and made a bunch of public appearances – here and abroad – to talk about the book. Have you gotten a charge out of it? Have you learned anything on the road that you didn’t expect?

Eric Klinenberg: I have! As you know, I spend a lot of time thinking about how scholars and universities can do a better job engaging the world, and NYU’s Institute for Public Knowledge, which I direct, is largely dedicated to that mission. Books provide occasions for all kinds of conversations – with academic readers, of course, but also with people outside the academy who are interested in ideas and with policy makers as well. This new book, about social infrastructure and the places that shape modern civic life, invites people to identify the most valuable local institutions in their own hometowns, and to consider how to strengthen the ones that have gone neglected. That means each time I visit another city or nation it’s a learning experience for me as well, because at minimum I discover social infrastructures that I hadn’t appreciated, and often I find out about the larger set of issues that structure political life, too.

For instance, last week I was in Chicago, which is my native city, and I asked audience members to raise their hand if they’d been to a library in the past month. Nearly everyone did – or at least a greater proportion than in any place I’ve spoken – and when I asked what was going on there the answer emerged quickly: Chicago libraries were the main places where citizens could vote early, and tens of thousands did. International trips are even more instructive. I recently spent a week on book tour in England, where austerity measures have threatened libraries in ways that few American communities have experienced, with volunteer workers stepping in to keep facilities open because there is so little public funding. I also spent a few days in Sweden, where support for public gathering places has diminished amidst a right-wing backlash against new immigrants. The book helped launched conversations that might not otherwise have happened.

Personally, the more powerful part of this book tour has been the experience of joining together with people who, like me, have gotten exhausted and despondent from the endless conversations about the current “situation,” which generally end without much serious consideration of what we should be doing or what kind of society we want to build. I make sure the book talks quickly become collective efforts to take on those questions. It’s difficult, because today it feels like the house is on fire and there’s not much point in doing anything other than trying to put it out. But taking the conversation to the next level is so important, and I’d like to see more social scientists leading us there.

C: A lot of media coverage related to the book has focused on public libraries. And a majority of your appearances have been in public libraries. And why not? They’re cool places! They also are your book’s prime example of social infrastructure at its best – when they’re appreciated for the multiple functions they can serve. But sometimes they’re not leveraged for their potential. As examples, in the book you contrast Columbus, OH, which voted for a tax to fund the elimination of fees for overdue books, with San Jose, CA, which cracked down on late fees because of “anti-tax ideology.” Why do cities like Columbus “get it” – at least in your view – while other municipalities don’t?

EK: It's simple, really: A modest increase in local taxes produces a massive public benefit, one that everyone shares, regardless of whether they personally use the library. Why? Because libraries have become a crucial part of the safety net, the educational system, and the local democracy as well. If you’re a child, a parent, or a caretaker, you probably use the library to promote early reading and meet other people in your situation. If you’re homeless, you’re likely to go to the library when the shelter closes, because it’s safe, reliable, welcoming, and warm. The same is true if you’re mentally ill, or old, or unemployed and looking for work. It’s true if you’re an immigrant looking for a place to learn English or study for a citizenship test. It’s true if you’re a teacher looking for a place where your students can do research or borrow books. It’s true if you can’t afford a computer, or internet access. It’s true if you’re a teenager in search of a quiet place to study, or a social place to play video games because it’s better than being home alone or in the streets.

Why do some cities, including San Jose, fail to make the kinds of investments that help libraries become more accessible? I think it’s because too many cities are led by people who don’t recognize the enduring value of libraries. Too many American elites – in policy, business, and, philanthropy – see them as luxuries, rather than as critical social infrastructures. I hope my book helps them change their perspective.

C: We have to ask you about the 2016 presidential election. Most remember where they were that night. You and your family were here with us in CASBS’s main gathering space. Did that election impact the way you thought about things for the rest of your fellowship year? Did it infiltrate the research for and/or writing of the book, whether in explicit or implicit ways?

EK: It affected all of the fellows, so much so that many of us complained we needed a “do-over” at CASBS, because we were so depressed by the result!

I’d already outlined the plan for the book when Trump won the election, but the result gave me a greater sense of urgency and purpose. As dark as things were – and are – I didn’t want to write a book complaining about the situation to people who already shared my point of view. Instead, I took up the challenge of trying to understand the underlying conditions that shape social cohesion, which meant searching for places that either support or undermine interactions at a very local level. That grew into a larger project, of examining the way physical places and organizations contribute to civic life.

I struggled to find the voice for this in the first months after the election, but I found it by early spring. Thankfully, I was at CASBS, and so I had a level of time, space, and intellectual camaraderie that every scholar dreams about, and just the right amount of stimulation from the world down the hill as well.

C: To be sure, as you note in the book, many things were trending in an unfavorable direction long before the 2016 election: climate change, inequality, class mobility and insecurity, trust in institutions, never-ending culture wars, social media echo chambers, volunteerism, political gridlock, and so forth. You observe that the “social order now feels precarious” and our “collective project is in shambles.” Ultimately, “the systems we build in coming years will tell future generations who we are and how we see the world today. If we fail to bridge our gaping social divisions, they may even determine whether that ‘we’ continues to exist.” We come away from your book feeling, on balance, well, a little crestfallen given the current state of affairs out there. You too? Without question, the book is a rousing, inspiring call to action. But are you generally optimistic or pessimistic?

EK: It's been interesting to see all the reviews of the book that call me an optimist. Palaces is most definitely a blueprint for building a better, more democratic, and more sustainable world, and I do believe we have a chance to get there. But – sorry! – I’m not glib about the current situation. Getting out of the current crises is going to require a lot of work. I think universities could play a major role in this, but not if we stick to business as usual and act as if we have the luxury of time. The threats of climate change, fascism, and nativism, to name just a few of the problems I work on and worry about, do not give us the luxury of staying up on Alta Road [home of CASBS] and talking (or writing) to each other. We need to engage.