Anderson, Nelson Reflect on Equality, Equity at Sage-CASBS Award Event

Attendees took advantage of a unique opportunity to listen to two of the nation’s most towering intellects brought together for the first time, in the same place.

The place was CASBS, and the occasion was the 2023 Sage-CASBS Award Lecture hosted on November 16, 2023, and featuring Elizabeth Anderson of the University of Michigan and Alondra Nelson of the Institute for Advanced Study.

CASBS, in partnership with Sage, announced Anderson and Nelson as winners of the seventh Sage-CASBS Award in June 2023. Readers can refer to the announcement to learn about their remarkable careers of accomplishments, accolades, and publications that preceded their CASBS appearance. Their impressive CVs, detailing honorary degrees and elections to national academies and societies, now share one more thing in common.

Established in 2013, the Sage-CASBS Award recognizes outstanding achievement in the behavioral and social sciences that advances our understanding of pressing social issues. It underscores the role of the social and behavioral sciences in enriching and enhancing public discourse and good governance. Past winners of the award include Daniel Kahneman, psychologist and Nobel laureate in economic sciences; Pedro Noguera, sociologist and education rights activist; Kenneth Prewitt, political scientist and former U.S. Census Bureau director; William Julius Wilson, sociologist and celebrated scholar of poverty, inequality, and race; Carol Dweck, social psychologist and foundational figure in the development of mindset science; and Jennifer Richeson, psychologist and authority on the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dynamics of intergroup interactions.

For the first time in the life of the award, there are two winners. And though Anderson and Nelson were chosen on individual merit by the award selection committee[i], their pairing at the Nov. 16 event was inspired, as they both illuminate public understandings and advance national discourse on how systems of power and social structures perpetuate societal inequalities and inequities. In fact, equality and equity, whether as concepts or as deployed in practice, figured prominently at the event.

Two winners also allowed the award event host, CASBS, to experiment with its traditional award lecture format. Rather than the usual single award lecture of up to an hour or so, on Nov. 16 Anderson and Nelson delivered shorter 20-minute award talks – a tough task for most scholars – then joined together in a conversation moderated by Woody Powell, who served as the Center’s interim director through most of the 2022-23 Sage-CASBS Award cycle.

The Center played with format in another way. Rather than waiting until the end of the program, as in past award cycles, CASBS director Sarah Soule presented the award plaques and checks to Anderson and Nelson minutes after kicking off the event. Soule’s introduction of each winner effectively ended in mini-celebrations.

“This is the best job ever,” Soule exclaimed while handing out the hardware.

Elizabeth Anderson is the Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, the John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women’s Studies, and the Max Shaye Professor of Public Philosophy at the University of Michigan. In her expansive work, she explores the interactions of social science with moral and political theory, how we learn to improve our value judgments, the epistemic functions of emotions and democratic deliberation, and issues of race, gender, and equality. Her latest book, released in September 2023, is Hijacked: How Neoliberalism Turned the Work Ethic Against Workers and How Workers Can Take It Back.

Outside academia, Anderson is most known, thanks to a 2019 profile in The New Yorker, as “The Philosopher Redefining Equality.” And during her Nov. 16 talk at CASBS, she returned to fundamental themes of equality – namely, what it is and why we should even want it.

Whether it’s among people or channeled through institutional structures, social (rather than economic or distributive) equality is a relational ideal, as Anderson explained, inextricably linked with freedom in egalitarian thought. And whereas egalitarian thought typically has been sharp on critique or in contrasting social equality with social hierarchy, it has been less so in articulating positive ideals of equality.

She sketched a few examples of movement toward such ideals in different domains of life – shifts in some societies away from patriarchy, from dictatorship toward democracy, or from marginalized identities toward a status conferring greater dignity and respect – but stressed process over outcomes.

“There are works in progress,” Anderson noted. “We never end our development and deeper and fuller and richer articulation of the content of these ideals, all with the aim of supporting the freedom in relations of equality for everyone.”

Of course, those situated at the lower rungs of a social hierarchy would want equality, or certainly much less inequality, and there is evidence suggesting that more equal societies are more trusting, less violent, experience less crime, and just healthier overall. But what about the people at the top?

This is one of the more interesting things about egalitarian thinking, in Anderson’s estimation: it manifests sympathy for them, too, “because they also are not served well by social hierarchy, however much they think they are.” She cited the ignorance and emotional stunting of resulting social isolation as well as the arrogance, vanity, and boasting about vices emblematic of moral corruption among some at the top of the social hierarchy.

To knowing chuckles among attendees, and without naming names, she invited them to think of apt examples in our contemporary landscape…

Later in the program, during moderated discussion with Woody Powell, Anderson added, after providing historical data and examples (citing noted economic historian Gavin Wright), that those at the top of the social hierarchy may think they gain by maintaining their status, but in fact one’s life “gets enriched by empowering and opening up opportunities for less advantaged people. It’s a lesson we keep on having to learn again and again.”

After general concurrence from Alondra Nelson on the data but pushback on translating that lesson into outcomes, Anderson acknowledged what many in the audience already understood – forward steps of progress often are met by some sort of backlash in that slow crawl of progress.

“This is characteristic of how the contest between equality and inequality happens,” she said. Process over outcome.

* * *

Social scientists use terms such as equality (or, more often, inequality or discrimination) to refer to degrees of social stratification and their impacts. But what of equity? Whether as an analytic construct or in public discourse, what is it and what is it good for?

That’s the entry point for Alondra Nelson, the Harold F. Linder Chair and Professor of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study. Her work lies at the intersection of science, technology, power, and social inequality; with most of her contributions situated at the intersection of racial formation and social citizenship, on the one hand, and emerging scientific and technological phenomena, on the other. One notable example is her 2016 book The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation after the Genome.

Recently, Nelson entered the public consciousness through her high-profile service in the Biden Administration from early 2021 to early 2023, first as deputy director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), then as OSTP acting director and deputy assistant to the president. Among other things, she helped lead efforts on federally funded research accessibility, scientific integrity, and on a bill of rights for protecting privacy, enhancing transparency, and promoting equity in the use of artificial intelligence technologies – the “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights.” Nature selected Nelson as one of ten people who helped shape science in 2022.

It is this government service at the highest policy level, placed in dialogue with her academic training, that inspired most of Nelson’s remarks at CASBS on Nov. 16.

Nelson agreed with Anderson that scholars are used to thinking in terms of equality or, more likely, its negative: hierarchies and inequalities, whether in terms of prejudice, discrimination, social stratification, poverty, or wealth. She agreed, furthermore, that social scientists typically are great at characterizing and analyzing, say, wealth inequalities, but often put forth less energy into proposing correctives and thoroughly explaining implications.

While work on inequalities will, of course, continue, Nelson pivoted and considered equity – while only partly derived from academic scholarship – as a more capacious sociopolitical category that simultaneously indexes both aspiration and redress.

Why capacious? On the Administration’s first day in January 2021, President Biden issued his first (symbolically notable as a “cornerstone commitment,” as Nelson called it) Executive Order (EO) on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Section 2 of that EO broadly defines equity as “the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.”

Now that encompasses a lot, quite possibly (in)equality itself! Whether the definition illuminates more than it obscures, Nelson did not judge. Rather, her point was to acknowledge that “in a kind of social science sense, it creates this sort of master category that absorbs the other ways that we might think about inequality, or equality…equity becomes this huge, capacious category and therefore…very sociopolitically potent.”

Nelson sought to harness that potency to think through with the audience the apparent power of equity – as a term, as a concept, as exhibited by the EO – in relation to equality in the popular imagination.

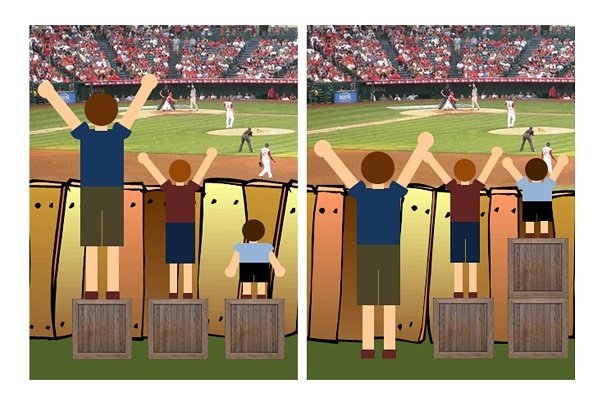

She did so in the form of an equally potent meme, first created in 2012 by University of Cincinnati professor Craig Froehle, and the many variations of it that traveled to various corners of the internet and into public discourse, powerful in both its simple aesthetics as well as the political traction it gained.

What do the left and right panels of the graphic image depict? As Nelson (and Froehle) explain, no firm consensus has emerged; so far it has depended on one’s perspective and quality of argument. The version most of us have seen asserts that the left panel depicts Equality while the right panel depicts Equity. Yet here are just a few examples of alternate interpretations that have circulated in virtual public squares in recent years:

Left panel

Equality of opportunity

Equality to a conservative

Equality

Equality

Equal treatment

So, then, just what are equality and equity? Again, Nelson did not stand before the audience to serve as arbiter. She had a larger point.

“What’s so powerful about this image is that it’s in action…there’s an activity that’s happening…[and]…something can be done about it in this moment,” said Nelson. “It’s calling the viewer to do something in a particular way…that I think other kinds of representations of, say, structural inequality don’t quite do.”

In fact, she continued, accounts of (often generations of compounded) structural inequality seem, in her assessment, “quite foreboding, because you feel like there’s nothing you can quite do.”

But the meme suggests actions that can be taken right now, while a game – or myriad social interactions in life that the meme can represent – are under way.“

It suggests that inequality or inequity is a sort of pattern,” she continued, “that is clear and that can be seen and…can be mitigated – I think social scientists note that it’s a bit harder than that – and that action can and must be taken; that there’s an avenue for redress if one wants to take it, and it’s showing you what the clear action for redress is.”

During the moderated conversation with Woody Powell, Anderson and Nelson both agreed that they were thinking in broadly compatible ways. However, Nelson added, “I think equity as a social-political category is making a second move…there’s an assumption of equality that has not been manifest in outcomes…therefore, other interventions must be made to mitigate or…create something that looks like the positive ideal of equality.”

Nelson admitted she felt “very curious” to be advocating for a concept she had not used in her prior academic work. But she did it: she outed herself as a “sociologist of equity.”

“I’m actually quite interested and obsessed about finding out what it does in the world and how it does what it does in the world,” she said. “Obviously, having the President of the United States say equity is a thing…makes it a thing.”

For something like the “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights,” which advances the equity banner yet does not carry the weight of law like an Executive Order does, it is nevertheless impactful in part, according to Nelson, because copies of it were sent to schools and state legislators around the country, some of its principles incorporated into curricula and legislation.

“So, it gained traction because of the halo of the White House,” Nelson noted, “but it also was a document that was useful for people. It set forth principles, but in a way that are actionable and operationalizable.”

The Craig Froehle meme that Nelson discussed was created in 2012. It has traveled far and wide in the past dozen years or so. But has consensus begun to emerge on what the meme signifies or what corresponding actions it may precipitate? In what direction will the meme travel in the next dozen years? Likewise, will the meaning of “equity,” as embodied in the Biden Administration’s January 20, 2021 EO (or the OSTP’s October 2022 AI blueprint) retain its potency and remain an actionable “thing” on, say, January 20, 2025, or January 20, 2029 – dates otherwise known as Inauguration Day?

Many of us, along with Alondra Nelson, are quite interested about what equity does in the world between now and then, and how.

View the 2023 Sage-CASBS Award Lecture event video on YouTube.

View the interview with the 2023 Sage-CASBS Award winners on YouTube.

[i] The 2023 Sage-CASBS Award selection committee consisted of Woody Powell, the Jacks Family Professor of Education, Stanford University, and former interim director, CASBS; Blaise Simqu, CEO of Sage; Robert Gibbons, the Sloan Distinguished Professor of Management and Professor of Organizational Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Anna Grzymala-Busse, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Professor of International Studies and Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University; and Jennifer Richeson, the Philip R. Allen Professor of Psychology, Yale University, and previous winner of the Sage-CASBS Award.