What fellows feel, Stanford’s director of architecture beautifully explains: the distinction the Center's buildings and grounds enjoyed at their creation and continue to enjoy today, more than seven decades later.

For seven decades, from the early post-War period continuing a quarter into the 21st century, CASBS fellows have worked on and produced scholarship that has helped develop and advance the social and behavioral sciences. The fellows themselves are primary characters in the Center’s enduring and unfolding story.

But CASBS fellowship is residential. The physical context in which those scholars undertake their work – the Center’s buildings and grounds – is itself an important character in telling the Center’s story in full. (How CASBS even landed at its location is a rollercoaster story unto itself.) Signs of this were evident just months after the Center welcomed its first class in September 1954 – CASBS was the subject of an attractive spread in the February 1955 issue of Arts and Architecture. And it remains plainly evident today; first-time visitors to the Center can’t help but remark on its beautiful architecture and landscaping, nestled atop a bucolic, somewhat hidden hilltop not far from the Stanford Dish and the front nine of the Stanford golf course.

Fellows experience it on a deeper level. The Center as a physical place gradually seeps into the bones and psyches of those fortunate enough to spend nine or ten months in residence day-to-day as CASBS fellows. And from there, it seeps into the work. Proof of this lies, among other places, in the acknowledgments found in countless books written by CASBS fellows and entered into the Center’s renowned Ralph W. Tyler Collection. They describe a “halcyon setting,” the “serenity of the rustic setting,” “surpassingly beautiful surroundings,” and a “special ambience” that – especially when intertwined with the intellectual stimulation the Center and each fellows cohort facilitates – contribute to “ideal conditions” or “inspiring working conditions [and] delightful atmosphere” resulting in the “nearest thing to a scholar’s heaven I can imagine” and “a magical place to which [fellows] owe much merely for the privilege of being there.”[1]

Thankfully, aside from changes in interior décor and barely-visible traces of various maintenance and upgrade projects over the years, CASBS’s buildings and grounds of 2025 would look practically unchanged to William Wurster and Thomas Church, the Center’s original architectural and landscape designers, and to Morely Baer, who photographed the Center for the 1955 Arts and Architecture spread. Remarkably, a new building on the Center’s campus, completed and dedicated in 2023 and the first addition since 1954, enhances rather than disrupts the harmony among structures, landscape, and people that the mid-century designers envisioned. In fact, recent coverage in The Architect’s Newspaper notes that the new building and its immediate surroundings, by architectural firm Olson Kundig and landscaping firm SWA, take cues and learn from Wurster’s mid-century design.

In the subjective hearts and minds of generations of fellows and visitors alike, CASBS certainly enjoys a singular distinction. But what about the wider environment in which CASBS is situated? How distinct is CASBS as a physical place as it relates, say, to the architectural wealth found just within the Stanford University ecosystem, never mind beyond it?

In November 2024, Sapna Marfatia, Stanford University's Campus Preservation Architect and Director of Architecture, delivered a presentation to a convening of CASBS’s board of directors addressing exactly how and why the Center is “a place apart.” Her talk was such a hit with board members and staff there to witness it that we asked Sapna to come back and elaborate upon some of the principal issues and themes she covered, including some fantastic historical perspective. She agreed to share some images and diagrams from her presentation as well.

CASBS: Let’s start with the Center’s general setting. What strikes you?

Sapna Marfatia: The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) occupies a unique perch above Stanford — both literally and figuratively. While the main campus stretches across the flatlands, CASBS sits quietly in the foothills, surrounded by a more natural, bucolic landscape. This elevated position offers not only a physical remove from the bustle of campus life but also a contemplative vantage point — one that invites reflection and perspective.

Interestingly, this hilltop site was the original vision for Stanford University. Frederick Law Olmsted, the university’s original landscape architect, had proposed placing the campus in the foothills. But Leland Stanford, a railroad magnate with a practical mindset, rejected the idea. He believed building on a hill would be too difficult for future growth and insisted on siting the university on the adjacent flatlands.

In 1901, the hill became the site of Alta Vista, the family home of Charles G. Lathrop — Jane Stanford’s brother and the university’s treasurer and business manager. After the death of Lathrop’s widow in 1947, the land was deeded back to Stanford. The main house was demolished in 1954 to make way for the Ford Foundation Research Center, which would later become CASBS.

Today, standing on this hilltop, one is treated to a breathtaking view of the university below. The panorama captures not just the campus, but its evolution — set against the backdrop of the San Francisco Bay and the distant hills beyond. Whenever I visit CASBS, I make a kind of pilgrimage to this spot. I take photographs of the main campus, seeing it anew each time — from above, in context, in conversation with its surroundings. It’s a perspective that deepens my appreciation for Leland Stanford’s decision to build on the plains. Had he chosen otherwise, we might not have this extraordinary view.

Conversely, when viewed from Lake Lagunita, CASBS reveals its quiet presence. Unlike the more imposing Alta Vista mansion that once stood here, CASBS blends into the hillside. Remarkably, the hill itself has remained largely unchanged for over 125 years. The architecture of CASBS doesn’t dominate the landscape — it respects it. It’s a silent intervention, one that honors the natural contours of the land.

Below: Lake Lagunita and Stanford main campus as seen from CASBS, Feb. 6, 2023. (CASBS files)

CASBS: It’s interesting – and perhaps metaphorical – that from our hilltop we easily can see the main campus, yet it’s not so easy for the main campus to see us. It gives another meaning to the title of your presentation to the CASBS board – A Place Apart. Perhaps more contradistinction than distinction?

Sapna Marfatia: When I asked CASBS board members to close their eyes and recall Stanford’s architecture, their minds were instantly transported to Palm Drive and the Main Quad — a quintessential Stanford image. They envisioned thick sandstone walls and red terracotta roof tiles, both hallmarks of the Richardsonian Romanesque style with Mission Revival influences. This distinctive architectural language, established during Stanford’s founding period (1875–1899), evokes a sense of permanence, tradition, and grandeur.

In contrast, CASBS was conceived nearly fifty years later, during a time of rapid post-War expansion on college campuses across the country. San Francisco Bay Area collegiate architecture of this era reflected national trends that favored innovation over historical revival. California, in particular, adapted these modernist movements to suit its milder climate and more informal cultural ethos.

Thus, CASBS presents a quiet but powerful architectural counterpoint. Instead of thick, defensive stone walls, we find expansive glass façades that dissolve the boundary between interior and exterior. Instead of the heavy, iconic terracotta rooflines viewed from a palm-lined promenade, CASBS’s low-slung roofs blend seamlessly into the landscape.

The architecture and landscape here do not demand attention — they invite presence. They whisper rather than shout. The buildings are modest in scale, nestled within mature trees and native plantings. The result is a campus that feels contemplative, human-scaled, and deeply integrated with its natural surroundings. Beautifully evocative, it is a place that welcomes you in gently, encouraging reflection rather than spectacle.

CASBS: During your presentation, you mentioned that CASBS is one of the few properties on campus recognized for its historical significance from the post-War era. From what I understand, it’s not just historically important — it’s also the only building in your survey area that stands out architecturally within what’s called the Second Bay Tradition. That seems pretty unique. Could you talk more about what sets CASBS apart and why it holds such a special place in that architectural narrative?

Sapna Marfatia: As part of our campus-wide evaluation of historically significant architecture, a section focused on the post-War period — approximately 1950 to 1974 — and identified three key architectural styles within the Regional Modernism theme. These include Brutalism, known for its bold, sculptural use of concrete; Mid-Century Modern, a refined offshoot of the International Style characterized by expansive glass surfaces and clean, solid lines; and the Second Bay Tradition, which spans roughly from 1930 to 1960 and emphasizes natural materials like redwood, with designs that blend seamlessly into the landscape.

Among the 44 post-War properties we examined — including 21 in the Second Bay Tradition — CASBS emerged as the only one deemed architecturally significant. In 2021, it was formally evaluated and ultimately recorded by the Santa Clara County Office as a historic district eligible for listing on the California Register. CASBS was recognized as a distinguished example of Second Bay Tradition collegiate architecture from the post–World War II era, and as the work of master designers William Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons (WBE), and landscape architect Thomas Church.

What makes CASBS particularly compelling is its deeply contextual design — a thoughtful, localized response that stands in contrast to the more universal, placeless approach of Mid-Century Modernism. Many architects from the European Bauhaus movement, who helped shape Mid-Century Modern architecture in the U.S., especially in cities like Chicago, favored adaptable glass-box designs that could be placed virtually anywhere, regardless of climate or culture. The Second Bay Tradition, by contrast, embraced modernism while rejecting the idea of a one-size-fits-all aesthetic. Architects like Wurster responded to California’s unique climate and materials, crafting buildings that felt rooted in their environment.

At CASBS, this philosophy is evident. The low rooflines, subdued materials, and the way the buildings seem to dissolve into the surrounding landscape are all intentional. These are not 'look at me' buildings — they are 'feel comfortable' buildings. CASBS doesn’t seek to make a bold architectural statement; instead, it creates a space that is grounded, welcoming, and in harmony with its setting. That’s what makes it so exceptional. It’s also worth noting that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hanna House, located in the Faculty Residence area of the Stanford campus, is another architecturally significant structure from this era — an iconic example of Modernism that holds its own place in history.

Top photo taken August 29, 2024 (Bill Tatham for SWA Group landscape architects, used with permission)

Bottom photo taken April 24, 2025 (Katelyn Tucker for CASBS)

View more examples of the Center's low rooflines and structures dissolving into the landscape at the end of this interview.

CASBS: What attributes on its campus make CASBS an architecturally distinct example of the Modernist era?

Sapna Marfatia: It is worth noting that CASBS was designed by two influential figures of the Modernist era: architect William Wurster and landscape architect Thomas Church. Their collaboration was not only close but deeply symbiotic, producing a design language that helped define the regional architecture of California. Together, they championed natural, low-maintenance, and livable environments — gardens and buildings that felt effortless and deeply human. Church had a deep understanding of architecture and believed that the landscape surrounding a home should create spaces for living, playing, and working. Wurster, in turn, had a keen sensitivity to landscape, designing buildings where the transition from interior to exterior felt seamless and intuitive. Their complementary visions resulted in environments that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also profoundly livable.

To appreciate the architectural significance of CASBS, we must first understand a key distinction between art and architecture. While art often acts as a catalyst for change, architecture typically mirrors the culture and technologies of its time. It tends to be conservative, relying on proven methods rather than pushing boundaries. However, the devastation of the twentieth-century wars — particularly in Europe — disrupted this pattern. The widespread destruction sparked a fundamental question: should societies rebuild using traditional styles and materials, or should they break from the past and forge a new architectural language?

Modernism emerged as a bold answer to that question. It introduced not only new aesthetics but also new materials — concrete, steel, and glass — while traditional materials like stone became scarce and costly. This shift was not merely practical; it was philosophical. Today, we take floor-to-ceiling glass walls for granted. But in the post-war era, replacing thick, fortress-like stone walls with transparent glass was revolutionary. It marked a dramatic shift in how buildings related to their environment. The boundary between inside and outside began to dissolve. Nature was no longer something to be kept at bay — it became part of the architectural experience.

CASBS embodies this Modernist ethos. Each building features an entire wall of glass, allowing scholars to remain visually connected to the surrounding landscape while working indoors. During my talk, several scholars confirmed that this seamless integration of interior and exterior fosters a contemplative, almost monastic atmosphere — one that deeply enhances their intellectual focus and creative work.

CASBS: And so William Wurster is emblematic of the shift you mentioned?

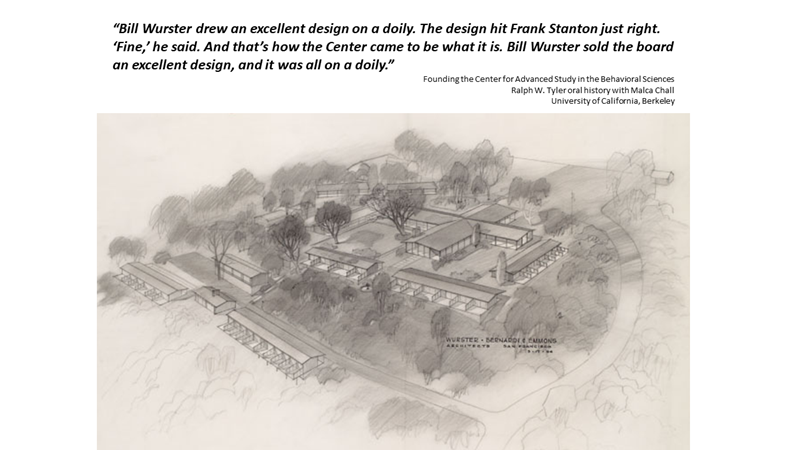

Sapna Marfatia: Through my research on William Wurster’s design for CASBS, I discovered a compelling narrative of architectural intuition and mastery. When Wurster first arrived at the Alta Vista site, he didn’t begin with sketches or blueprints. Instead, he spent two full days walking the land, quietly observing and absorbing its natural rhythms, topography, and vegetation. This immersive process allowed him to internalize the site’s essence so deeply that, when he finally began to draw, the design emerged with striking immediacy and clarity. This was not merely a product of instinct, but the result of decades of experience. By 1954, Wurster was at the mature height of his career, and his firm — Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons — had become one of the most respected architectural practices in the country, known for its award-winning work in both residential and institutional design.

The CASBS project, which received the American Institute of Architects First Honor Award in 1956,[2] exemplifies Wurster’s genius for site-sensitive architecture. His conceptual sketch, remarkably close to the final built form, reveals a design that delicately inserts study buildings, terraces, and central convening spaces amongst mature oak trees and the few remaining agricultural structures from the Lathrop era. This surgical precision preserved the site’s naturalistic setting and expansive views — features that remain central to the ethos of CASBS today. What stands out in my research is how Wurster didn’t just design buildings; he composed a spatial experience. He understood that architecture is not only about the structures themselves, but also about the spaces between them — the courtyards, walkways, and thresholds that foster reflection, dialogue, and community.

This brings me to a central insight: Wurster’s design embodies the container-content relationship in architecture. He conceived of CASBS as a container precisely shaped by the nature of its content — an intellectual community dedicated to deep thought, interdisciplinary interactions, and quiet contemplation. The architecture supports this mission not through grand gestures, but through subtle, deliberate choices: the orientation of terraces to capture light and views, the placement of buildings to encourage both solitude and serendipitous encounters, and the preservation of the landscape to ground the experience in a sense of place. In this way, CASBS is not just a campus — it is a carefully crafted vessel for the life of the mind. Board members and fellows in attendance at the meeting affirmed that, as behavioral scientists, they found the spatial arrangement genuinely inspiring — fulfilling its intended purpose.

CASBS: Yes. Unplanned, spontaneous interactions among fellows occur in several places, particularly in the central area, and at all hours. But the lunch hour is a time when it’s guaranteed that all fellows congregate at the same place at the same time. It’s probably also meaningful that the dining patio is the highest point at which one can stand on the entire CASBS campus.

Sapna Marfatia: Absolutely — food is a powerful social catalyst, and at CASBS, Wurster designed the architecture to support and amplify this. At the heart of the campus lies a cruciform building that serves as the central hub for daily interaction. From above, it appears as a single cross-shaped structure, but in reality, it is composed of three distinct buildings. Each arm of the cross houses a key function: the Margaret Levi meeting room, the library reading room, the dining room, and the main administrative office. These spaces are arranged so that one side of each wing contains the primary room, while the opposite side is dedicated to circulation — hallways and walkways that encourage movement and informal encounters.The cruciform layout also shapes the outdoor environment in a meaningful way. It divides the surrounding landscape into four distinct courtyard quadrants, each with its own atmosphere and purpose. These courtyards are not just leftover spaces — they are thoughtfully designed extensions of the indoor rooms they border. For example, the courtyard labeled “3” in the diagram below is a dining patio that opens directly from the dining room. Positioned at the highest point on the CASBS campus, this patio offers sweeping views and a comfortable outdoor setting that naturally extends lunchtime conversations into the open air. The intersecting walkways that connect the buildings’ wings and courtyards further enhance the sense of flow and connectivity, making spontaneous meetings and casual exchanges a regular part of daily life at the Center. Brilliantly designed, the central building encourages vibrant intellectual exchange through meaningful conversations and collaborations, while the monastic study cells along the campus periphery offer quiet spaces for deep introspection and focused thought.

CASBS: The photo at lower left (in the image above) and at right hint at the sightline one gets as one is walking from the parking lot toward the front office. The sightline goes straight through the property – the south-to-north shaded red vertical path in your diagram – toward San Francisco Bay and beyond. It’s striking, unmistakable, and intentional.

Sapna Marfatia: And this reveals another counterpoint. Analyzing the entry sequence and framed views reveals how CASBS stands in deliberate contrast to the spatial logic of Stanford’s Main Quad. At Stanford, the iconic quad is defined by a vast, open central space surrounded by large, imposing buildings. This arrangement emphasizes monumentality and can make individuals feel small, as the architecture dominates the landscape. CASBS, by contrast, inverts this spatial hierarchy. William Wurster placed the main buildings at the center of the site, creating a compact, human-scale core that fosters interaction and community.

As mentioned before, from this central hub, open spaces — courtyards and terraces — radiate outward, forming a series of outdoor rooms that are closely tied to the functions of the buildings they border. These structures are modest in scale and closely interconnected, with circulation corridors that encourage movement and spontaneous encounters. Each wing of the cross opens onto a distinct courtyard, reinforcing the seamless relationship between interior and exterior space.

As you note, one of the most striking spatial experiences occurs upon arrival. As visitors walk from the parking lot toward the front office, they encounter a carefully framed sightline — aligned along a south-to-north axis—that cuts through the campus and opens toward the distant view of San Francisco Bay. This visual corridor not only orients the visitor but also underscores the openness and transparency of the site.Beyond the central area, smaller wings extend outward to house the fellows’ individual studies. These studios are slightly removed from the communal core, offering quiet, contemplative spaces for focused work. The transition from the active center to the tranquil periphery is smooth and intentional, supporting both collaboration and solitude. The entire campus is scaled to the human experience — never overwhelming, always inviting.

The CASBS campus stands as a model of human-centered design. No single building dominates the landscape; instead, the entire site feels approachable, balanced, and thoughtfully scaled to the individual. Wurster’s design begins at the heart of the campus—where people gather, converse, and connect—and extends outward in a carefully orchestrated composition. This central-to-peripheral layout creates a sense of both intimacy and openness, grounding the experience in community while allowing space for reflection and retreat. The result is a campus that feels simultaneously expansive and deeply personal.

Fellows retreat to their studies along the campus periphery to engage in quiet, focused work. Photo taken November 17, 2021. (CASBS files)

CASBS: What are your thoughts on the new building on the CASBS campus, completed and dedicated in late 2023, and how it fits with the 1954 CASBS campus. As you know, it houses three convening spaces of different sizes, another IT office, and a few other things. It has quickly become a very functional space, as the courtyard – now called the Hitz Courtyard, actually – in front of the new building has been upgraded and those using the new building, in particular, spill out onto that courtyard’s tables and benches. It also has become the go-to space for parties, receptions, and other events when weather permits.

Below: Another view of the Hitz Courtyard, September 5, 2024. (Photo by Bill Tatham for SWA Group landscape architects, used with permission)

Sapna Marfatia: Integrating new architecture into an existing, well-defined context is no small feat. When done with sensitivity to the site’s character and scale, it can enhance the sense of place — but when done poorly, it can just as easily diminish it. At CASBS, much credit goes to Olson Kundig, the architects behind the recent addition. Tom Kundig approached the project with humility, aiming to create a building that was ego-less — one that would honor, not overshadow, William Wurster’s original design.

To achieve this, Olson Kundig absorbed Wurster’s sense of proportion and scale with remarkable fidelity. The decision to site the new building in the former front parking lot, just to the right of the original complex, was pivotal. This area — marked as Quadrant #2 (in a previous slide, above) — had long been an underutilized service space, visible upon arrival but never fully activated. Though originally conceived as a courtyard adjacent to what evolved into the back side of the dining room, it lacked definition and purpose. The placement and orientation of the new building enclosed this space, transforming it into a functional, inviting and front-facing courtyard.

The new structure’s width, exterior walkway, and material expression deliberately mirror Wurster’s original study building, creating a subtle architectural dialogue. The result is a beautifully understated intervention — more landscape element than architectural statement — that sits quietly in the foreground, allowing the integrity and balance of Wurster’s design to remain fully legible and appreciated.

Finally, as part of the Center's ongoing evolution, the dining room underwent a thoughtful refresh in 2024 — an intentional step toward honoring its Bay Area tradition and modern heritage. CASBS approached the transformation with care, ensuring the remodel echoed the aesthetic captured in archival photographs from that era. The result is a space that not only reflects the past but also inspires the future.

Interview conducted by Mike Gaetani

Photos noted as CASBS files by Mike Gaetani

View early images of CASBS in the Stanford Digital Repository, Stanford University Libraries

[1] Example quotes drawn from, respectively, W. Richard Scott, Institutions and Organizations (1995), p. xi; Abram Amsel, Frustration Theory: An Analysis of Dispositional Learning and Memory (1992), pp. vii-viii; Albert Rees, The Economics of Trade Unions (1962), p. ix; William Gamson, et al, Encounters with Unjust Authority (1982), p. x; David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1983 (1975), p. 18; Marija Gimbutas, The Balts (1963), p. 11; Charles P. Kindleberger, A Financial History of Western Europe (1984), p. xviii; and William H. Riker, The Theory of Political Coalitions (1962), pp. ix-x.

[2] Wolf Von Eckardt, ed. (1961). Mid-Century Architecture in America: Honor Awards of the American Institute of Architects, 1949-61. The Johns Hopkins Press, pp.154-156.

View more examples of the Centers buildings and grounds. All photos below by 2022-23 CASBS fellow Cameron Campbell, used with permission.